- Introduction

- Protean Plants

- Odyssean Origins

- Protei Botanica

- The Protean Typus and Delicate Empiricism

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works Cited and Further Reading

Hinweg zu Proteus! Fragt den Wundermann:

Wie man entstehn und sich verwandlen kann.

(To Proteus! Go ask that wondrous man:

How one can form and change across time’s span.)

– Faust II (WA I/15:160, lines 8152–53)

Introduction

Since his appearance in Homer’s Odyssey, Proteus has had a rich afterlife among the figures and metaphors of Western thought. In an episode from the Odyssey known as the “binding of Proteus,” the Spartan king Menelaus wrests vital information from Proteus while the elusive sea god hides in a diverse array of natural forms—animals, elements, and plants. Two major trends of interpretation arose from the Homeric myth. On the one hand, Proteus’ transformations were negatively associated with inconstancy, semblance, and falsity. Plato’s Euthydemus, for instance, compared Proteus’ shapeshifting antics to sophistical “jugglers’ tricks”1 that dazzle the mind but conceal the truth. In a Christianized reiteration of the Platonic critique, Erasmus Francisci’s Der Höllische Proteus (1690; The Hellish Proteus) summoned Proteus to imagine the “betrieglichen Gestalt-Wechsels”2 (deceptive transformations) of Satan that lead humanity into doubt and false belief. On the other hand, Proteus’ mutability, as well as the etymological relation of his name to protos or “first,” spurred more favorable associations among early modern alchemists and natural philosophers with the idea of materia prima or prime matter: a primordial, formless, and shared substrate of natural beings that remains constant amid their changes.3 In this vein, Proteus became a symbol of an ideal unity underlying material transformation and diversity, be it the diversity of natural elements and taxa or—as in the historical studies of Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)—the diversity of cultural, linguistic, and poetic forms.4

Goethe’s imagination of “Proteus” in the context of his botanical studies and beyond aligned most closely with the latter tradition. The leaf or Blatt, he realized in 1787, was the “wahre Proteus” (WA I/32:44; true Proteus): a dynamic formal archetype concealed in both the development of individual plants and the global diversity of plant species. From these early forays in botanical science to the end of his life, Goethe drew on Proteus’ fabled metamorphoses to express his vision of a common but concealed morphological unit that mediated the constancy and changes of natural forms. I would, however, caution against interpreting this instance of “Dauer im Wechsel” (constancy in change)—to cite the title of Goethe’s famous poem from 1803—as a privileging of identity over difference or being over becoming. As I suggest throughout this entry, recovering the specifically “protean” element in Goethe’s theory of metamorphosis, including both its literary and environmental contexts, sheds light on how he erodes the boundaries between these metaphysical binaries.

Protean Plants

In a letter to Herder from May 17, 1787, Goethe announced his hypothesis that “in demjenigen Organ der Pflanze, welches wir als Blatt gewöhnlich anzusprechen pflegen, der wahre Proteus verborgen liege, der sich in allen Gestaltungen verstecken und offenbaren könne” (WA I/32:44; Scientific Studies 327; in that plant organ which we ordinarily call the leaf a true Proteus is concealed, which can hide and reveal itself in all sorts of configurations). The “true Proteus” that Goethe had discovered on April 17 in the public gardens of Palermo encapsulated his vision of a basic morphological structure shared by all botanical forms. On the one hand, this discovery covered the level of species, as Goethe sought to understand the global diversity of plant life as an expression of the protean leaf’s metamorphoses in differing contexts and climates.

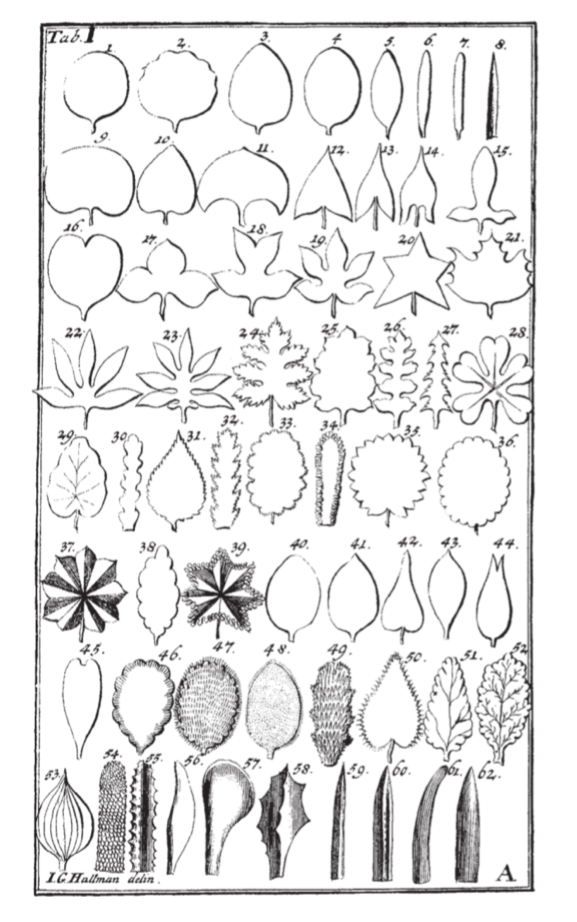

On the other hand, Goethe’s botanical writings also foregrounded instances of “rückschreitende Metamorphose” (WA II/6: 64; Metamorphosis of Plants 65; retrogressive metamorphosis) that revealed an essential non-linearity in the development of individual plants (see figs. 1a and 1b). Like Homer’s Proteus, Goethe’s “leaf” was a site of disorienting convergence between constancy and change, homogeneity and diversity, individual and species—a juncture where these apparent opposites flowed into one another inseparably.6

Proteus, in this sense, symbolically encapsulated Goethe’s defining idea in the field of botany, often summarized under the dictum “Alles ist Blat” (WA II/7:282; All is leaf). Far from a fixed signifier indicating the specific foliar appendage of the stem leaf, Goethe’s protean Blatt represented an “allgemeines Wort” (WA II/6:92; general word) fluid enough to register the radical polyvalence of plant metamorphoses. His major botanical study, The Metamorphosis of Plants (1790), concluded by noting that

Dasselbe Organ welches am Stengel als Blatt sich ausgedehnt und eine höchst manigfaltige Gestalt angenommen hat, zieht sich nun im Kelche zusammen, dehnt sich im Blumenblatte wieder aus, zieht sich in den Geschlechtswerkzeugen zusammen, um sich als Frucht zum leztenmal auszudehnen. (WA II/6:91)

The organ that expanded on the stem as a leaf, assuming a variety of forms, is the same organ that now contracts in the calyx, expands again in the petal, contracts in the reproductive apparatus, only to expand finally as the fruit. (Metamorphosis of Plants 100)

Similar to his 1787 letter to Herder, Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants emphasized the leaf’s protean play of concealment and self-revelation in plants’ observable, nameable organs: stem leaf (Stengelblatt), petal (Blumenblatt), sepal (Kelchblatt), and even the fruit and seed. Each variation of the Blatt represented for Goethe a splintered glimpse of the “true” Proteus’ total activity, which simultaneously infused and transcended its particular manifestations. In this sense, Gordon Miller proposes that the protean leaf, as “the crucial concept coursing and pulsing throughout Goethe’s botany,” is neither a static nor immediately visible organ but rather an index of the “vibrant field of formative forces” underlying all possible metamorphoses of plants, their species, and indeed the entire vegetable kingdom.7 Indeed, the proliferation of Blatt-words in Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants suggests that this “vibrant field” could also be understood semiotically—as a disseminative force of language itself that forms the text’s constellation of leaf-signifiers.

We can better locate the uniqueness of Goethe’s position by considering discussions of it in the contemporary field of ecocritical plant studies. What Heather I. Sullivan and James Shinkle call the “protean ‘leafness’”8 integral to Goethean botany—the idea that the leaf embodies a fundamental foliar form—has recently come under fire in Michael Marder’s Plant Thinking (2013). While Marder esteems the deconstructive gesture in Goethe’s inversion of “origin” (seed) and “supplement” (leaf), he also seeks to uproot Goethe’s “lamentable imposition of identity onto the plant, whose differences in form are traceable to the self-same substratum underwriting them.”9 Given Goethe’s refraction of vegetal identity/difference through the mythopoetic lens of Proteus, however, it bears asking if this conceptual dichotomy is as “crystal clear”10 as Marder suggests. Rather, one might also consider how Goethe’s protean leaf reactivates, in Cassirer’s phrase, the “fluid and fluctuating”11 meaning structures of myth, where imagination, affect, and conceptuality commingle without definite theoretical commitments. Goethe’s turn to the Homeric figure of Proteus, which I consider more closely in the following section, bespeaks a moment of contact with something irreducible to scientific terminology or metaphysical binaries: an entity—or better yet, a becoming (ein Werdendes; see LA 10:131)—at once constant and dynamic, particular and universal, linguistic and natural.

Odyssean Origins

Already on March 25, 1787, while walking along the Tyrrhenian coast of Naples, Goethe reported “eine gute Erleuchtung über botanische Gegenstände” (WA I/31:75; an epiphany over botanical matters). His journey across the sea to Sicily, moreover, had a transformative effect on his relationship to nature: “Hat man sich nicht ringsum vom Meere umgeben gesehen,” he mused after landing in Palermo, “so hat man keinen Begriff von Welt oder von seinem Verhältnis zur Welt” (WA I/31:90; Those who have never seen themselves surrounded on all sides by the sea have no conception of the world or their relation to it; see also WA IV/44:129). Though Goethe certainly faced anxiety, alienation, and seasickness onboard the ship, one cannot miss the sense of novelty and wonder permeating his experience. Alongside dramatic descriptions of the shift in elemental scenery (WA I/31:82), Goethe’s travelogue includes gleeful observations of dolphins (WA I/31: 85) and his first forays into watercolor painting (WA I/31: 91)—a medium that he later drew on to depict retrogressive metamorphosis (see figs. 1a and 1b), one of the key pieces of evidence for his “protean” understanding of plant metamorphosis.

When Goethe first visited Palermo’s public garden, the site of his protean epiphany, he effused that the surrounding maritime scenery “rief mir die Insel der seligen Phäaken in die Sinne sowie ins Gedächtnis” (WA I/31:106; conjured the island of the blessed Phaeacians to my senses and my memory) and inspired him to purchase a copy of Homer’s Odyssey. The epic accompanied him on daily trips back to the seaside garden where he read a daily “Pensum” (WA I/31:147; workload) of Homer and worked on Nausikaa, a “dramatische Concentration der Odyssey” (WA I/31:198; dramatic concentration of the Odyssey) that focused on Odysseus’ sojourn in Phaeacia. Surrounded by scenes of the sea—literally and literarily—Goethe gained a new perspective on his surroundings. Palermo’s coastal milieu and “das alles umgebende Meer” (the all-encompassing sea), he wrote to Herder, transformed the Odyssey into “ein lebendiges Wort” (WA I/31:238–39; a living word; see also WA I/31:199).

On April 17, the same day that Goethe reported discovering his “true Proteus” to Herder, he also wrote to Friedrich von Stein: “Ich habe viel, viel Neues gesehen, erst hier lernt man Italien kennen. Ich wünschte dir, daß du die Blumen und Bäume sähest, und wärest mit uns überrascht worden, als wir nach einer beschwerlichen Überfahrt am Ufer des Meeres die Gärten des Alcinous fanden” (WA IV/8:211; I have seen many, many new things; one truly becomes acquainted with Italy here. I wish that you could see the flowers and trees, and that you had shared our surprise as we discovered by the seashore, after an arduous passage, the garden of Alcinous). Goethe’s now famous identification of Palermo’s public garden with the mythical “Garten des Alcinous” (WA I/31:147; garden of Alcinous) evidence how his immersion in Sicily’s Homeric seascape saturated his perception and imagination of the natural world during this critical period of his botanical studies.

Alcinous’ garden appears in book seven of the Odyssey, during the Phaeacian leg of Odysseus’ travels. As Odysseus goes to entreat the Phaeacian king Alcinous for aid, he beholds a glorious orchard particularly striking for its ensemble of diverse species and phases of plant life. Indeed, the passage was so striking to Goethe that he not only outlined a similar verse for his unfinished drama, Nausikaa (see WA I/10:418), but composed a German translation from Homer’s Greek:

Wohlgewachsen trugen daselbst die gründenden Bäume

Birnen, Granaten und Äpfel, die Äste glänzten gebogen,

Süße Feigen fanden sich da und Beeren des Ölbaums.

Niemals mangelt es hier an Früchten. Im Sommer und Winter

Bringet Zephir die einen hervor und reifet die andern.

Apfel eilet nach Apfel dem süßen Alter entgegen,

Birn’ nach Birn’ und Feige nach Feigen und Traube nach Trauben.

Denn es stehen Reben gepflanzt im sonnigen weiten

Raum, es trocknet daselbst ein Theil der Trauben am Stocke,

Andere lieset man ab und keltert sie, andere nähern

Langsam der Reife sich noch und andere blühen der Zukunft.

Immergrünend wächst das Gemüs’ auf zierlichen Beeten

Wohlgeordnet zuletzt und schmücket das Ende des Gartens. (WA I/4:327)

Here luxuriant trees are always in their prime,

pomegranates and pears, and apples glowing red,

succulent figs and olives swelling sleek and dark.

And the yield of all these trees will never flag or die,

neither in winter nor in summer, a harvest all year round

for the West Wind always breathing through will bring

some fruits to the bud and others warm to ripeness—

pear mellowing ripe on pear, apple on apple,

cluster of grapes on cluster, fig crowding fig.

And here is a teeming vineyard planted for the kings,

beyond it an open level bank where the vintage grapes

lie baking to raisins in the sun while pickers gather others;

some they trample down in vats, and here in the front row

bunches of unripe grapes have hardly seen their blooms while

others under the sunlight slowly darken purple.

And there by the last rows are beds of greens,

Bordered and plotted, greens of every kind,

glistening fresh, year in, year out.12

In Alcinous’ garden, all stages of plant development from bud to fruit are present at once. Odysseus’ gaze remains unrestricted to a single slice of the life cycle—he bears witness, in a single moment, to the entire series of growth and transformation. The incredible variety of botanical forms is unified by a common vitality beautifully captured in Goethe’s present participle immergrünend (“always greening”), but without their differences being subsumed under a totalizing identity. Rather, Homer’s poetic juxtaposition of diverse—often directly contrasting—species and specimens generates the impression of the whole as a togetherness (Zusammenhang) of discrete parts.13

Goethe’s later description of the leaf as the “true Proteus” to Herder was symptomatic of the Homeric milieu in which he began rethinking botany and natural morphology, more generally. Proteus appears shortly before Odysseus’ arrival in Phaeacia; in the Odyssey’s fourth book, the Spartan king Menelaus recounts wrestling with the elusive sea god, who attempts to escape by mutating into an array of elemental, vegetal, and animal forms:

The old god still remembered all his tricks [dolies… technes],

and first became [genet] a lion with a mane,

then snake, then leopard, then a mighty boar,

then flowing water, then a leafy tree.

But we kept holding on: our hearts stood firm.

At last that ancient sorcerer grew tired[.]14

Homer’s phrase “tricks” or “cunning [. . .] techniques”15 (dolies… technes) no doubt played a decisive role in shaping the interpretive ambiguity that characterizes Proteus’ reception in philosophical history. On the one hand, dolies, (“deceitful”) appears to support Plato’s alignment of Proteus’ metamorphoses with illusion: subduing Proteus symbolizes one’s overcoming of false appearances in the quest for certain knowledge. With Heidegger’s “Question Concerning Technology” in mind, on the other hand, one could read Proteus’ technes within the conceptual arena of poeisis, episteme, or even aletheia, that is, a pre-Platonic conception of truth as disclosure.16 The sea god’s transformations, intending to trick and deceive Menelaus, equally open a view onto the fluid kinship between natural creatures and elements—a kinship irreducible to simple “identity” precisely because it reveals itself in Proteus’ becoming-different from himself. Whereas Plato reads this as a masquerade of Proteus’ true being, Homer’s verb genet (from gignomai, “to become” or “come into being”) foregrounds acts of genesis that disseminate identity across a plethora of forms and formative processes.

Such a view, which I believe more accurately represents Goethe’s stance, also aligns with early moderns and Renaissance thinkers who discovered in Proteus “a symbol of nature’s vitalism and mutability,”17 and more specifically, alchemical notions of prime matter or prima materia. George Sandys (1578–1644), for example, writes that

Proteus physically is taken for the First Matter, converting into all diversity of formes; which againe resolve into their owne originall: and said to bee the sonne of Neptune, because the operation and dispensation of Matter is exercised chiefly in liquid bodies. So… both plants and living creatures are produced from the selfe same Matter, and the matter it selfe converted into Elements; which the Ancient expressed by Proteus his multiplicity of changes.18

What distinguishes this viewpoint from Goethe is its insistence that be there be something before nature’s changes—some stable “originall” into which things can be resolved. With Goethe, this idea is turned on its head: Change itself is primary while stability is an abstraction from more fundamental formative processes that vitalize even inorganic or “dead” entities like stones. (Tellingly, it is in a geological essay that Goethe details his “dynamic” vision of nature, which attends to “den Moment des Entstehens, das lebendige Spiel der Elemente und ihrer Anziehungen.” WA II/10:78; the moment of emergence, the vital play of elements and their attractions; emphasis added.19) For Goethe, in other words, Proteus is less a symbol of some eternal being underlying the transformations of material nature than an embodiment of what Jennifer Caisley calls the “vibrant, ever-changing”20 spirit of matter (Materie) itself.

From Palermo onward, the latter vision of Proteus shaped Goethe’s understanding of vegetal metamorphosis. For Goethe, Proteus stood for the fluid play between being and becoming, identity and difference, that unsettles self-sameness (see WA II/6:12). While Goethe does attribute a sense of sameness to the “idea” (WA II/6:12; Idee) of living beings like plants, Goethean “ideas” are anything but stable; rather, they mimic the dynamic activity of the creature under consideration. In his key essay on gegenständliches Denken (objective thinking), Goethe recalls how “die Idee der Pflanzenmetamorphose in mir aufging” (WA II/11:62; the idea of plant metamorphosis arose [or sprouted] in me) during his Italian journey—a cleverly ambiguous phrase which imagines the idea’s genesis in terms of germination. Goethe’s notes on Jan Evangelista Purkyně’s New Subjective Reports about Vision, moreover, describe how the ideal plant appeared in his imagination as a “hervorquellende Schöpfung” (WA II/11:283; streaming creation) that was impossible to fix in any stable form. Its specifically fluid dynamic of transformation recalls not only Proteus’ aquatic element but also his own metamorphosis into “flowing water” in Homer’s Odyssey.

With time, Goethe’s protean viewpoint extended beyond his botanical studies. In 1805, two decades after his trip to Sicily, Goethe cited Proteus’ appearance in the Odyssey as a “Symbol der Natur” (WA Abtheilung für Gespräche 2:6; symbol of nature) during a conversation with Friedrich Wilhelm Riemer.21 In Goethe’s final and perhaps most experimental published work, Faust II, Proteus’ appearance during the Classical Walpurgis Night powerfully staged the workings of a concealed but ubiquitous metamorphic principle of nature:

Thales

Wo bist du, Proteus?

Proteus bauchrednerisch, bald nah, bald fern.

Hier! und hier! (WA I/15: 164, line 8227)

Thales: Where are you Proteus? / Proteus (ventriloquizing, now close by, now far away): Here! And here!

Recalling Goethe’s observations of marine life while sailing to Sicily, Proteus then transforms into a dolphin to carry the still-forming Homunculus through the Aegean Sea—a scene which Rabea Kleymann has recently called the “poetische Inszenierung eines Hindurchdringens der Form durch die davorliegende Mannigfaltigkeit” (poetic staging of form penetrating through the surrounding manifold).22 Similar to his appearance in the Odyssey, Proteus in Faust II offers a figuration of the emergence or poiesis of natural forms while also reflecting on poetry’s own form-giving power. Beyond this, Faust II beautifully illustrates how deeply Goethe’s idea of Proteus was saturated by the mythopoetic and environmental imagination; from Goethe’s Sicilian odyssey in 1787 to the end of his life in 1832, Proteus remained a creature of the sea.

Protei Botanica

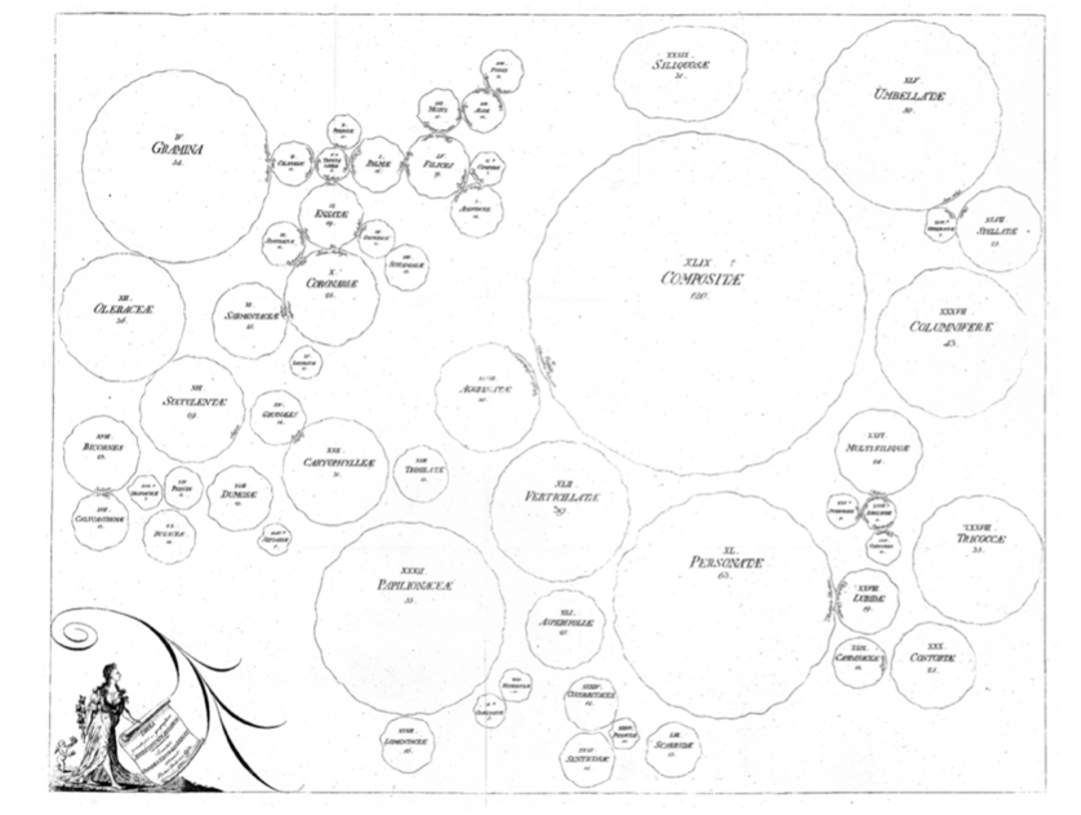

Goethe’s turn to Proteus and the sea represented a symbolic break from the “terrestrially biased”23 botanical system of his predecessor, Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeus’ Philosophia Botanica (1751), which Goethe studied intently during his early forays into botany, imagined plant species as “territories on a geographical map”24 and construed taxonomic boundaries as precisely definable according to observable characteristics like leaf shape. This territorial vision of plant life was later materialized by Linnaeus’ student, Paul Giseke, whose “Genealogical-Geographical Table of Plant Relations” (Tabula genealogica-geographica Affinitatum Plantarum, 1790) depicted botanical taxa as bounded circular islands afloat in an ocean of white space (see fig. 2). The blank spaces of Giseke’s Tabula (“the ‘ocean’ between the ‘islands’”25) represented gaps in knowledge that remained to be discovered and mapped. Subsumed under the colonial imagination, Linnaean botany and its terrestrial metaphors sought to subdue a crisis of botanical knowledge brought about Western expansion: between 1600 and 1800, the number of plant species documented by European botanists exploded nearly ten-fold, from six to fifty thousand.26

Goethe’s interest, in contrast, lay precisely in the “oceanic” regions between Linnaeus’ taxonomic territories. His epiphany of the leaf’s protean and fluid metamorphoses, in particular, guided his eventual turn from Linnaeus’ geographical imagination:

Wenn ich an demselben Pflanzenstengel erst rundliche, dann eingekerbte, zuletzt beinahe gefiederte Blätter entdeckte, die sich alsdann wieder zusammenzogen, vereinfachten [. . .] und zuletzt gar verschwanden, da verlor ich den Muth irgendwo einen Pfahl einzuschlagen, oder wohl gar eine Gränzlinie zu ziehen. Unauflösbar schien mir die Aufgabe, Genera mit Sicherheit zu bezeichnen. (WA II/16:117)

When I discovered leaves on the same stem that appeared at first rounded, then notched, then almost feathered before contracting again, simplifying their form, […] and finally disappearing—I lost all courage to drive in a stake or even draw a boundary line. The task of determining genera with certainty appeared insoluble.

Though Goethe leaves unnamed the particular specimen—Craig Holdrege suggests the wild radish27—his point is clear: common descriptors of Linnaean nomenclature like “rounded” (orbiculatum), “notched” (emarginatum), and “feathered” (pinnatifidum) reduce the leaf’s metamorphic dynamic to an arbitrary point in the plant’s life cycle (see fig. 3). Confronted with the leaf’s protean transformations through diverse forms within a single life span, Linnaeus’ geographical imagination of botanical taxonomy as an act of boundary demarcation breaks down.

With reference to contemporary ecocritical trends, Goethe’s protean leaf muddies the waters between “green” and “blue” paradigms. While Dan Brayton diagnoses ecocritical scholarship’s “chlorophilia—an inability to look beyond the imagery of the land and its leafy green cloak,”28 Goethe urges us to question the self-evident “greenness” of leaves. Goethe’s articulation of vegetal life in terms of a “blue” concept like Proteus constitutes what Melody Jue would call an act of “conceptual displacement” that “estranges the terrestrially inflected ways of theorizing and thinking to which we have become habituated.”29 While Jue, a trained scuba diver, literally immerses herself undersea to unsettle surface concepts, Goethe’s Proteus grew from his immersion in maritime environments and literature. Moreover, by drawing on Proteus to rethink Linneaus’ terrestrially biased metaphors, Goethe evokes Jue’s “amphibious perspective,”30 which productively inhabits spaces of tension and transgression between the “blue” and “green.”31

The Protean Typus and Delicate Empiricism

Through Goethe’s botanical studies, Proteus also became a central symbol for his idea of the type (Typus), a basic schema for describing general classes of natural beings such as plants, insects, or mammals.32 In a note on plant physiology from the period of the Italian Journey, Goethe reflected on the

Große Schwierigkeit, den Typus einer ganzen Klasse im Allgemeinen festzusetzen, so daß er auf jedes Geschlecht und jede Species passe; da die Natur eben nur dadurch ihre genera und species hervorbringen kann, weil der Typus, welcher ihr von der ewigen Notwendigkeit vorgeschrieben ist, ein solcher Proteus ist, daß er einem schärfsten vergleichenden Sinne entwischt und kaum theilweise und doch nur immer gleichsam in Widersprüchen gehascht werden kann. (WA II.6:312–13)

Enormous difficulty of fixing a general type for an entire class so that it applies to every genus and every species. Nature can only bring forth its genera and species because the type, which is prescribed through eternal necessity, is such a Proteus that it eludes even the sharpest comparative mind. One can hardly grasp it partially and yet it can only be grasped, so to speak, in contradictions.

The difficulty of fixing generic types, as Goethe imagined it, once again evoked the Homeric myth of the “binding of Proteus.” Goethe’s question, deeply connected to his idea of the protean leaf, was how to determine a consistent formal archetype for a natural being which, like Proteus, “sich ewig verändert und sich vor unsern Beobachtungen bald unter diese, bald unter jene Gestalt verbirgt (WA II.6: 318; constantly changes and conceals itself in various guises before our observations).

Goethe answered this question in a 1796 study on comparative anatomy, “Anwendung der allgemeinen Darstellung des Typus auf das Besondere” (Application of the General Description of the Type to the Particular) in which he returned to the myth of Proteus to articulate a theory of epistemological mimicry:

Nun aber müssen wir, indem wir bei und mit dem Beharrlichen beharren, auch zugleich mit und neben dem Veränderlichen unsere Ansichten zu verändern und mannichfaltige Beweglichkeit lernen, damit wir den Typus in aller seiner Versatilität zu verfolgen gewandt seien und uns dieser Proteus nirgend hin entschlüpfe. (WA II/8:18)

While we endure with the enduring, we must also learn to change our notions along with the ever-changing. Our thinking must become much more agile so that we are deft enough to follow the type in all its versatility and this Proteus never slips from our grasp. (Scientific Studies 121; translation amended)

This passage, which predates Goethe’s oft-cited saying that calls for a “zarte Empirie” (delicate empiricism) by over three decades, the figure of Proteus lies behind his vision of an empirical science “die sich mit dem Gegenstand innigst identisch macht und dadurch zur eigentlichen Theorie wird” (which makes itself utterly identical with the object, thereby becoming true theory; WA IV/45:11).

The “delicate” empiricism that Goethe began articulating in his writings on the protean Typus represented a stark departure from its Baconian counterpart, which emphasized the observer’s control over observed phenomena. Coincidentally, Francis Bacon also drew on the myth of Proteus to express his ideal of scientific method; however, in contrast to Goethe’s emphasis on mimicry and emulation, Bacon considered the binding of Proteus an allegory for the scientist’s mastery of nature by means of experimental instruments. Just as “Proteus [never] changes shapes till he was straitened and held fast,” Bacon wrote in The Advancement of Learning (1605), “so the passages of nature cannot appear so fully in the liberty of nature, as in the trials and vexations of art.”33 The dependency of Baconian empiricism on artificial instruments, Goethe believed, ultimately restrained the free development of perceptual, imaginary, and rational powers necessary to understand nature on its own terms.34 “Das ist eben das größte Unheil der neueren Physik,” Goethe reflected in 1808, “daß man die Experimente gleichsam vom Menschen abgesondert hat und bloß in dem, was künstliche Instrumente zeigen, die Natur erkennen, ja, was sie leisten kann, dadurch beschränken und beweisen will” (WA IV/20:90; Scientific Studies xvi–xvii; The greatest misfortune of modern physics is that its experiments have been set apart from man, as it were; physics refuses to recognize nature in anything not shown by artificial instruments, and even uses this as a measure of its accomplishments.)

Goethe and Bacon’s diametrically opposed interpretations of the Proteus myth not only reflect their differing interpretations of the relationship between the scientist and nature, but also their respective sources. Bacon cites Virgil’s Georgics, which describes Proteus’ subjugation through “brute strength” and “chains,”35 whereas in Goethe’s Homeric reference mimicry plays a central role. In Homer’s depiction of the binding of Proteus, specifically, the Spartan king Menelaus must first disguise himself as a seal to blend into the sea god’s elemental milieu. Just so for Goethe, grasping the protean elusiveness of the Typus presupposes a “metamorphosis of the scientist,” whereby one’s mode of thinking transforms to emulate the phenomena under investigation.36 As with Menelaus’ encounter with the sea god in Homer’s Odyssey, Goethe insisted, grasping the concealed Proteus in natural transformation demanded the scientist’s own becoming-protean.37

Conclusion

What makes a concept “philosophical”? A certain level of abstraction? Freedom from “lower” or “impure” forms of thinking like imagination, allegory, metaphor, and myth? If even the most seemingly abstract concepts like Locke’s substance are rooted in what Kant calls “indirect presentations” or “symbolic hypotyposes,”38 then under these criteria we would be hard pressed to find anyone who might reasonably count as a philosophical thinker at all. And if Geoffrey Bennington is correct that our “concept of what a concept is in general” is itself “defined metaphorically,”39 we could just as well throw out the notion of a “philosophical concept” altogether. This is nonsense, of course; there are philosophers, just as there are philosophical concepts, because we talk, write, and think about them—because we are constantly at pains to understand and define them. So perhaps, more simply, a philosophical concept is one which provides an impulse to do that kind of talking, writing, and thinking that we call “philosophical.” Proteus, no doubt, is one such concept. From Plato to Goethe (to Bacon to Herder to Schelling to Bennett and beyond), “Proteus” and the “protean” have shaped and reshaped philosophical understandings of nature, science, knowledge, and the self.

For Goethe, in particular, Proteus played a key role in that realm of his philosophical thinking associated with the study of morphology. It was a concept which helped him work through and articulate the conceptual entanglements of being and becoming, particularity and universality, and subject and object that he encountered in his studies of plant metamorphosis and natural metamorphoses in general. As I hope to have shown in this entry, the philosophical energy that Goethe drew from this concept was often due to its incredibly unabstract nature. It was a concept won from his own wrestling with literature and life—a concept he approached like a Spartan, “stinking of salt-bred seals.”40

- Plato, Laches, Protagoras, Meno, Euthydemus, translated by W. R. M Lamb (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1977) 437. See William E. Burns, “‘A Proverb of Versatile Mutability’: Proteus and Natural Knowledge in Early Modern Britain,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 32, no. 4 (2001): 969–80, here 971. ↩

- Erasmus Francisci, Der Höllische Proteus, oder Tausendkünstige Versteller (Nürnberg: 1695) “Vorrede” (Preface). ↩

- See Burns 972. ↩

- See Johann Gottfried Herder, Werke in zehn Bänden. Band 1. Frühe Schriften 1764–1772, edited by Ulrich Gaier (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1985), 23: “So verwandelte sich diese Pflanze [d.h., die Sprache], nach dem Boden der sie nährte, und der Himmelsluft, die sie tränkte: sie ward ein Proteus unter den Nationen” (Thus this plant [i.e., language] transformed according to the soil that nurtured it and the air it breathed: it became a Proteus among nations). ↩

- Craig Holdrege, “Goethe and the Evolution of Science,” In Context 31 (Spring 2014): 10–23, here 18. ↩

- See Ronald Brady, “Form and Cause in Goethe’s Morphology,” in Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal, edited by Frederick Amrine et al. (Boston: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1987), 257–300, here 272. ↩

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Metamorphosis of Plants, translated by Gordon Miller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009) xix. See Gabriel Trop, “Kraft (Force),” in Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 59–73. ↩

- Heather I. Sullivan and James Shinkle, “The Dark Green in the Early Anthropocene: Goethe’s Plants in Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären and Triumph der Empfindsamkeit,” Goethe Yearbook 26 (2019): 141–62, here 152. ↩

- Michael Marder, Plant Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life (New York, NY: Columbia UP, 2013) 82. ↩

- Marder 82. ↩

- Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man: An Introduction to a Philosophy of Human Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2021) 76. ↩

- Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Robert Fagles (Penguin, 1996) 183. ↩

- See Ross Shields, “Zusammenhang (Nexus),” Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): “The difficulty presented by Goethe’s concept of Zusammenhang is that the relation of part to whole that it describes cannot be reduced to either of these terms: although the whole can be said to condition its parts (as in a system), it does not precede, but emerges from their combination (as in an aggregate).” ↩

- Homer, Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson (New York, NY: Norton, 2018) 166. ↩

- Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Robert Fagles (Penguin, 1996) 138. ↩

- Martin Heidegger, Basic Writings (Harper San Francisco, 1977) 294–95. ↩

- Burns 972. ↩

- In Burns 974, ↩

- See Goethe’s conversation with Eckerman from February 13, 1827, where he explains that “Die Mineralogie ist daher eine Wissenschaft für den Verstand, […] denn ihre Gegenstände sind etwas Totes, das nicht mehr entsteht” (Mineralogy is thus a science for the understanding, for its objects are dead, that is, they no longer take form; WA Abtheilung für Gespräche 2:6, 14). The point here is not that minerals are “dead” because they are inorganic but rather because the formative processes which shaped them have come to a close. Goethe immediately goes on to explain that the objects of meteorology, though certainly inorganic, are nonetheless “etwas Lebendiges, das wir täglich wirken und schaffen sehen” (something living whose activities and operations we observe everyday; WA Abtheilung für Gespräche 2:6, 17; emphasis added). ↩

- Jennifer Caisley, “Materie (Matter),” Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 3 (Dec. 2022). ↩

- F.W.J. Schelling’s First Outline of a System of Philosophy of Nature [1799], written during a period of increased communication with Goethe, similarly likened nature’s “drama of a struggle between form and the formless” to an “ever-changing Proteus.” Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, translated by Keith R. Peterson (New York, NY: State University of New York Press, 2004), p. 28. On Schelling’s relationship with Goethe during this period, see See Dalia Nassar, The Romantic Absolute: Being and Knowing in Early German Romantic Philosophy, 1795–1804 (Chicago, IL: The U of Chicago P, 2013), 194–95. More recently, the protean vision of nature has found echoes in Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter, which describes an “ontological field” whose “differentiations are too protean and diverse to coincide exclusively with the philosophical categories of life, matter, mental, environmental.” Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010), 116–17. ↩

- Rabea Kleymann, Formlose Form: Epistemik und Poetik des Aggregats beim späten Goethe (Paderborn: Brill Fink, 2021), 225. ↩

- I understand “terrestrial bias” in line with Melody Jue, who describes the “normative habits of thinking and speaking about the world that belie our terrestrial acculturation.” Melody Jue, Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2020) 9. For more on the concept of terrestrial bias and how it relates to German thought and culture of Goethe’s time, see Benjamin D. Schluter, “Unexpected Bodies of Water: On the ‘Blue’ Goethezeit” in Goethe Yearbook, vol. 30 (2023): 147–54. ↩

- Carolus Linnaeus, Philosophia Botanica, translated by Stephen Freer (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003) p. 40. ↩

- Karen Magnuson Beil, What Linnaeus Saw: A Scientist’s Quest to Name Every Living Thing (New York, NY: Norton, 2019) 178. ↩

- Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2007) 198. See Carol Kaesuk Yoon, Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science (New York, NY: Norton, 2009), 51. ↩

- Holdrege 16. ↩

- Dan Brayton, Shakespeare’s Ocean: An Ecocritical Exploration (Charlottesville, VA: U of Virginia P, 2012), 37. ↩

- Jue 6. ↩

- Jue 5. ↩

- In this context, one might consider Goethe’s similarly blue-green concept of the Planzen-Ozean, which, as Sullivan and Shinkle write, “envisioned the vast landscape of green life as a ‘plant ocean’ in which insects are immersed in the same way that fish are immersed in the water of the sea,” and thus shaped a “concrete image and metaphor for the ecological participation of all living things.” Sullivan and Shinkle 141–42. Like the protean leaf, Goethe’s Pflanzen-Ozean is a concept perhaps best described as amphibious or blue-green: it draws on the ocean as a site of conceptual displacement to gain a new perspective on terrestrial life. ↩

- See David Wellbery, “Form (Form),” in Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 45–52, here 49. ↩

- Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning (New York, NY: Modern Library, 2001) 77. Similar interpretations of the binding of Proteus appear in Bacon’s The Wisdom of the Ancients and Preparative Toward a Natural and Experimental History. ↩

- See Joan Steigerwald, “Goethe’s Morphology: Urphänomene and Aesthetic Appraisal,” Journal of the History of Biology 35, no. 2 (2002): 291–328, here 296–97. ↩

- Virgil, Georgics, translated by Peter Fallon (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006), 88. ↩

- Frederick Amrine, “The Metamorphosis of the Scientist” in Goethe Yearbook 5 (1990): 187–222. For more on the topic of Goethe and epistemological mimicry, see Amanda Jo Goldstein, Sweet Science: Romantic Materialism and the New Logics of Life (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2017) 8; Leif Weatherby, Transplanting the Metaphysical Organ (New York, NY: Fordham UP, 2016), 297–99; Gunnar Hindrichs, “Goethe’s Notion of an Intuitive Power of Judgment,” Goethe Yearbook 18 (2011): 51–65, here 62; Thomas Pfau, “‘All is Leaf’: Difference, Metamorphosis, and Goethe’s Phenomenology of Knowledge,” Studies in Romanticism 49, no. 1 (2010): 3–41, here 8; Eckart Förster, “Goethe and the ‘Auge des Geistes,’” Deutsche Vierteljahrschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 75 (2001): 87–101, here 93. ↩

- Roland Borgards, “Proteus” in Liminale Anthropologien: Zwischenzeiten, Schwellenphänomene, Zwischenräume in Literatur und Philosophie, edited by Jochen Achilles, Roland Borgards, and Brigitte Burrichter (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2012), pp. 131–44, here 137. ↩

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment, edited by Paul Guyer, translated by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2000) 226. ↩

- Geoffrey Bennington, Kant on the Frontier: Philosophy, Politics, and the Ends of the Earth (New York, NY: Fordham UP, 2017), xxi. ↩

- Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Wilson, 166. ↩

Works Cited and Further Reading

- Amrine, Frederick. “The Metamorphosis of the Scientist.” Goethe Yearbook 5 (1990): 187–222.

- Bacon, Francis. The Advancement of Learning. New York, NY: Modern Library, 2001.

- Beil, Karen Magnuson. What Linnaeus Saw: A Scientist’s Quest to Name Every Living Thing. New York, NY: Norton, 2019.

- Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010.

- Bennington, Geoffrey. Kant on the Frontier: Philosophy, Politics, and the Ends of the Earth. New York, NY: Fordham UP, 2017.

- Borgards, Roland. “Proteus.” Liminale Anthropologien: Zwischenzeiten, Schwellenphänomene, Zwischenräume in Literatur und Philosophie, edited by Jochen Achilles, Roland Borgards, and Brigitte Burrichter, 131–44. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2012.

- Brady, Ronald. “Form and Cause in Goethe’s Morphology.” In Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal, edited by Frederick Amrine et al., 257–300. Boston: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1987.

- Brayton, Dan. Shakespeare’s Ocean: An Ecocritical Exploration. Charlottesville, VA: U of Virginia P, 2012.

- Burns, William E. “‘A Proverb of Versatile Mutability’: Proteus and Natural Knowledge in Early Modern Britain.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 32, no. 4 (2001): 969–80.

- Cassirer, Ernst. An Essay on Man: An Introduction to a Philosophy of Human Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2021.

- Förster, Eckart. “Goethe and the ‘Auge des Geistes,’” Deutsche Vierteljahrschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 75 (2001): 87–101.

- Francisci, Erasmus. Der Höllische Proteus, oder Tausendkünstige Versteller. Nürnberg: 1695.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. The Metamorphosis of Plants, translated by Gordon Miller. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

- Goldstein, Amanda Jo. Sweet Science: Romantic Materialism and the New Logics of Life. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2017.

- Hansen, Adolf. Goethes Metamorphose der Pflanzen. Geschichte einer botanischen Hypothese, vol. 1. Giessen: Verlag von Alfred Töpelmann, 1907.

- Heidegger, Martin. Basic Writings. Harper San Francisco, 1977.

- Herder, Johann Gottfried. Werke in zehn Bänden. Band 1. Frühe Schriften 1764–1772, edited by Ulrich Gaier. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1985.

- Hindrichs, Gunnar. “Goethe’s Notion of an Intuitive Power of Judgment.” Goethe Yearbook 18 (2011): 51–65.

- Holdrege, Craig. “Goethe and the Evolution of Science.” In Context 31 (Spring 2014): 10–23.

- Homer. The Odyssey, translated by Robert Fagles. New York, NY: Penguin, 1996.

- Homer, Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson. New York, NY: Norton, 2018.

- Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2020.

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of the Power of Judgment, edited by Paul Guyer, translated by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2000.

- Kleymann, Rabea. Formlose Form: Epistemik und Poetik des Aggregats beim späten Goethe. Paderborn: Brill Fink, 2021.

- Linnaeus, Carolus. Philosophia Botanica, translated by Stephen Freer. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

- Marder, Michael. Plant Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. New York, NY: Columbia UP, 2013.

- Nassar, Dalia. The Romantic Absolute: Being and Knowing in Early German Romantic Philosophy, 1795-1804. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 2013.

- Pfau, Thomas. “‘All is Leaf’: Difference, Metamorphosis, and Goethe’s Phenomenology of Knowledge.” Studies in Romanticism 49, no. 1 (2010): 3–41.

- Plato, Laches, Protagoras, Meno, Euthydemus, translated by W. R. M Lamb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1977.

- Schelling, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph. First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, translated by Keith R. Peterson. New York, NY: State University of New York Press, 2004.

- Schiebinger, Londa. Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2007.

- Schluter, Benjamin D. “Unexpected Bodies of Water: On the ‘Blue’ Goethezeit.” Goethe Yearbook 30 (2023): 147–54.

- Shields, Ross. “Zusammenhang (Nexus).” Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 121–40.

- Stearn, W. T. “The Background of Linnaeus’s Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology.” Systematic Zoology 8, no. 1 (1959): 4–22, here 7.

- Steigerwald, Joan. “Goethe’s Morphology: Urphänomene and Aesthetic Appraisal.” Journal of the History of Biology 35, no. 2 (2002): 291–328.

- Sullivan, Heather I. and Shinkle, James. “The Dark Green in the Early Anthropocene: Goethe’s Plants in Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären and Triumph der Empfindsamkeit.” Goethe Yearbook 26 (2019): 141–62.

- Trop, Gabriel. “Kraft (Force).” Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 59–73.

- Virgil. Georgics, translated by Peter Fallon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006.

- Weatherby, Leif. Transplanting the Metaphysical Organ. New York, NY: Fordham UP, 2016.

- Wellbery, David. “Form (Form),” in Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 45–52.

- Yoon, Carol Kaesuk. Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science. New York, NY: Norton, 2009.